Due to blue laws that banned theatrical activity on the Sabbath, the Hippodrome did not present its usual shows on Sundays. (I talk about that at the NY1920s website, here.) Organizations often rented the theater for mass meetings and fundraisers instead. One rally on December 5, 1909 was hosted by Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, a Mobile, Alabama native who used her great fortune and her platform in New York City society to support women’s suffrage and women’s rights in general.

Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, possibly on an ocean liner?, via the Library of Congress

The rally supported striking shirtwaist blouse makers. The 1909 Shirt Waist Strike, dubbed the “Uprising of the 20,000,” was an influential action in U.S. Labor History undertaken chiefly by young, Jewish women.

Jewish Women's Archive. "Women on Strike, 1909." (Viewed on March 22, 2024) <http://jwa.org/media/women-strike-1909>.

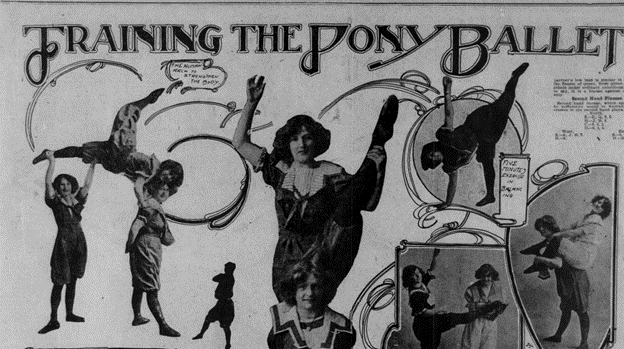

The strikers experienced a lot of harassment and full-on abuse from policemen. Some newspaper coverage was dismissive, suggesting that these young women just wanted a pay raise so they could buy frivolous things like fancy hats. Dress was a big part of the discourse about the strike, both in the press of the day and in current academic work inspired by Nan Enstad’s super-influential Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure.Check out the ladies below, who look super feminine in textured velvet and giant picture hats.

“Strike Pickets.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014684499/. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024.

The rally held at the Hippodrome supported their labor action, but it also put their work into dialogue with the women’s suffrage movement. Anna Howard Shaw, who worked with Susan B. Anthony in the nineteenth century, spoke at this event. The New-York Tribune noted that Rev. Shaw was speaking unofficially, though, because the National Woman Suffrage Association (of which she was the president) did not take a position on questions of labor. A snarky, sexist columnist said he “fail[ed] to trace the exact connection between the shirtwaist makers’ strike and woman’s suffrage. The prevalent idea that the feminine intellect is rarely logical seemed to be sustained.” But these were women who shared political ambitions that crossed class lines.

Girl Strikers, At Hippodrome, Cheered by 8,000 Sympathizers. Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library., Anna Marble Pollock scrapbook 1909-1910 season.

The Hippodrome rally attendance was 6,000 people at a minimum, and perhaps as many as 8,000 as the newspaper clipping reports. Even the low end was a higher number than the listed capacity of the Hippodrome, since many participants were seated onstage. The New York Times gave the most attention to the decoration of the venue’s interior:

"The stage settings were for a woman suffrage meeting. Flags of blue on both side walls carried the words in white, “Votes for Women.” Three small drops hung down from the curtain machinery, all carrying arguments in big letters which the girls in the rearmost seats could read. “We demand equal pay for equal work,” the audience read; and “Give women the protection of the vote.”

Theresa Malkiel Portrait. https://www.marxists.org/glossary/people/m/pics/malkiel-theresa.jpg. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024.

One of the women who attended on the labor side was Theresa Malkiel, socialist activist whose portrait is seen above. In her fictionalized account called The Diary of a Shirtwaist Striker, she talks about how the girls in her factory were excited to see Mrs. Belmont at the strike while she (the diarist) has some doubts about her sincerity. “I wonder what made her do it?” she writes, and then acknowledges “She must surely be better than the rest of her kind if she is willing to spend her money to help us girls rather than give a monkey dinner or buy a couple new pet dogs.” (The “monkey dinner,” given by socialite Mamie Fish, is described here.

Some of you might be wondering if this strike was at all related to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. The Shirtwaist Strike took place in late 1909 and early 1910. They had protested for higher wages and safer working conditions. But on March 25, 1911 a fire broke out on the top floors of the building, beyond where the firetruck ladders could reach. 146 women and girls died, some of whom surely took part in the strike the years before.

The Hippodrome continued to be a gathering point for women involved with suffrage and labor. Mrs. Belmont and Inez Mullholland, another wealthy women’s suffrage supporter, sponsored another Garment Worker’s Union meeting at the Hippodrome in January 1913.

“Women Rush Theatre, Despite Police Clubs.” New-York Tribune, 6 Jan. 1913, p. 14.

Labor rallies and benefits took place at the Hippodrome well into the 1930s. The International Ladies Garment Workers Union sponsored opera performances, raised funds for the Spanish Civil War, and celebrated May Day at the venue. The poster below is from a rally that took place on April 30, 1938. I love that the union continued to think of the Hippodrome as a place to champion their “efforts on behalf of working class freedom” and that those efforts developed to include fighting “against fascism, Nazism, reaction and war.”

ILGWU Web Site - Archives Broadsides. https://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/archives/broadsides/index.html?image_id=133. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024.